It may have been inevitable. Once Japanese whiskies started winning international awards and developed a fanatical base in the U.S., demand swiftly outstripped supply. Major producers were forced to allocate their suddenly popular brands and began emphasizing their blended malt and grain whiskies—as opposed to their headline-making single malts—in order to satisfy customers while they built up stocks.

However, because the Japanese whisky industry is largely unregulated, there are many other new Japanese whiskies entering the market, with unknown origins, blends, or production methods. Japanese distillers have always been allowed, for example, to blend imported and domestic whisky, and to export a blend made of 100 percent imported spirit and still label it as Japanese in origin. But the influx of elusive newcomers taking advantage of these lax rules has many distillers demanding change.

This lack of transparency has become an increasing source of confusion in the U.S. trade, as well as a potential threat to the category’s hard-won reputation, say producers, and it’s time to regulate industry practices and demand accountability.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning Daily Dispatch newsletter—delivered to your inbox every week.

A range of recent releases illustrate the challenge. Among them are a whisky made from a mix of malts and imported grain whiskies blended with filtered ocean water and finished in pine barrels (Umiki); a whisky made with a mash bill of 86 percent corn and 14 percent barley (Tenjaku); whiskies aged in Japanese cedar and sakura, a Japanese cherry wood (Kamiki); and a blend of new Scottish grain spirit aged entirely in Japan with Japanese malt (Akkeshi New Born Foundations 4). All are relatively new to the U.S. market but reveal dramatic differences in production.

A Slew of Experimental New Brands

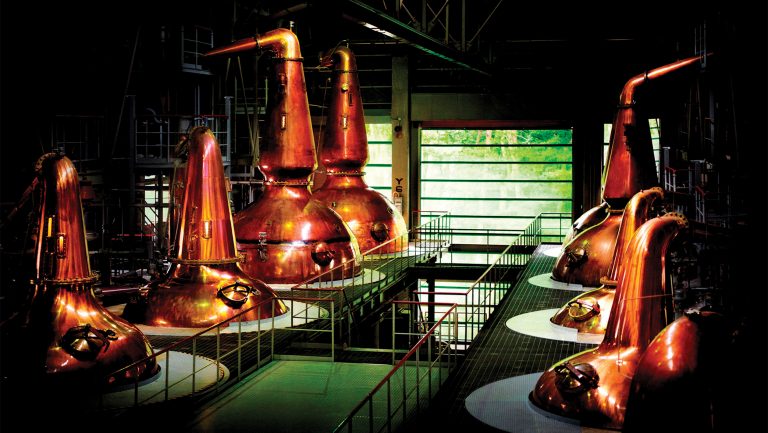

Now that approximately 30 distilleries, many of them fairly new, are operating in the country, more of these innovations and experimentations with wood types and ingredients can be expected, broadening what the American market has expected from the country. At the same time, whiskies from obscure sources are showing up with no provenance and little label information, causing concern about their impact, especially if consumers pay dearly and find they don’t compare favorably to whiskies from elsewhere. “Then they walk away thinking they don’t like Japanese whisky at all,” says Kris Eliot, the co-founder of High Road Spirits in Chicago, which imports whiskies from Chichibu (established in 2004), Mars (1949), and Eigashima (1888) distilleries, as well as newcomer Akkeshi (2016).

“We continue to see new brands from Japan and when you look up their address, it’s a WeWork office in Osaka rather than a distillery,” says Eliot. “There’s a geeky community that gets it but for the most part, most average consumers don’t. ”

“With Japanese whisky there is no legal definition except as regulated by tax law,” says Chris Uhde, the vice president of San Francisco-based importer ImpEx Beverages, which brings in spirits from long-established Japanese distilleries Fukano (a rice whiskey distiller established in 1823), Matsui Shuzou (1910), and Ohishi (1872). “Historically the industry has been based on blending, with houses blending malt with locally distilled or sourced grain. Not until 1968 did they actually have to have whisky in the bottle to call it whisky.”

More Category Clarity

Recently there have been rumblings within the world of Japanese whisky to make changes. The country’s most influential competition, the Tokyo Whisky and Spirits Competition, has set out new terms of definition they hope will clarify matters. Now there will be three categories: Japanese Whisky, which must be fermented, distilled and aged at least two years in Japan; Japanese New Make or New Born Whisky, a new category for whisky aged less than two years; and Japan Made Whisky, another new category in which some whisky made in Japan must be included in the blend.

Major producers are appealing to the government to organize taxes based more on provenance and are shunning events where questionable producers participate, according to sources.

“Discussions to classify and define various whiskies made in Japan are ongoing within the Japan Spirits & Liqueurs Makers Association, a government-approved organization of spirits producers, of which Nikka Whisky is a member,” says Emiko Kaji, Nikka Whisky’s international business development manager for Asahi Breweries, Ltd. “In the ongoing discussions, all whisky currently produced in Japan is being reviewed and considered to assure clarity for the consumer. Our position is to collaborate with the organization as a member, to set new standards based on long-term and realistic perspective.”

Before the COVID-19 crisis hit, a better working definition of Japanese whisky with supporting regulations was hoped for this year, but as of yet, nothing has changed.

“If the lack of rules to define Japanese whisky is causing misunderstandings among the consumers, we believe there is a problem that should be solved,” says Chicago-based Andrew Mondzelewski, the director of marketing for House of Suntory. “Continuous discussions on the definition of Japanese whisky have been taking place at the Japan Spirits & Liqueurs Makers Association, and once they have made a decision, we will keep to it.”

Blending, Innovation, and World Whisky

Meanwhile, major producers are both leaning on blended whiskies and offering limited-release malts. Nikka recently introduced Nikka Days and Beam Suntory is focused on blended whiskies Toki and Hibiki Japanese Harmony, while Nikka just imported limited-release Single Malt Yoichi and Single Malt Miyagikyo Apple Brandy Finishes. Buyers can probably expect more “world whisky,” a concept pioneered by Chichibu Distillery’s Ichiro’s Malt and Grain World Whisky, and recently followed in Japan with Suntory’s Ao, a blend of whiskies from five countries.

Ironically, the buzz created by those who “discovered” Japanese whisky in the past ten years is partly to blame for much of the confusion around what Japanese whisky is.

“A lot of it is definitely hype,” says Pedro Shanahan, the “spirit guide” for Los Angeles-based Pouring with Heart Thoughtful Bar Ventures. “But people have an attraction to it from a flavor perspective—the style is light and clean and specific and pretty sweet, so it appeals to someone who’s just getting into whisky. But we live in the age of information and they way people are so rabid about Japanese whisky there’s no way the facts are not going to come out.”

With lax regulations and little transparency, the liquid in the bottle may be different from what you expect

The reaction to the “revelation” that Japanese distillers have been using non-domestic whiskies to craft their wares annoys informed hands like Uhde. For years, he notes, iconic bourbon brands were being revived with sourced spirits, and even today, much of the rye sold under American brand names comes from Canada.

“What I’m hearing is a Western mentality take on what an Eastern product is,” he says. “Japanese whisky was never based on provenance; it was always about blending. People get a preconceived notion of what it should be, and when it doesn’t fit they raise an alarm. You need to understand the culture of what you’re buying, which in Japan has always been about blending. What’s in the bottle represents the brand, not the provenance of the spirit.”

Jack Robertiello, from Brooklyn, New York, has worked in and written about the world of drinking and eating for most of his adult life. He speaks frequently at conferences and judges competitions, and works in the industry as both a teacher and consultant.