A memorial service is a party no one wants to have a reason to throw. But with the nature of life, everyone inevitably must. It was my wife’s and my turn to put one on in early February when her mother passed away following a tough year-and-a-half-long battle with cancer. The first decision we made about the ceremony involved alcohol.

We punctuated her celebration of life with a Champagne toast, joined by everyone who packed our church to pay their respects. Though we used plastic communion cups in lieu of flutes, it was our way of honoring her favorite ritual. Every Sunday afternoon, she would sit on a patio, pop open a bottle of Champagne, and share it with family, friends, neighbors, or whoever happened to stop by and say hello. She never drank alone, either. Somehow, there was always someone to share the bubbly along with her joy.

As personal as it was, our decision to drink to commemorate the dearly departed wasn’t all that radical. Traditions around the globe inform us that imbibing in remembrance of those who passed is an honorable practice. Furthermore, the unique rituals surrounding the pouring and consumption of liquor can often symbolize the importance of relationships and coax happy memories, even as we mourn.

Don’t Miss A Drop

Get the latest in beer, wine, and cocktail culture sent straight to your inbox.

The most famous examples of in-memoriam drinking tend to have strong ties to culture, history, or both. These connections can provide insight into how others treat death’s sorrowful yet inevitable call, while also fortifying drinking rituals’ powerful ability to build and bind community. The traditions are bittersweet when viewed up close since a loved one’s death is involved, but when viewed from afar, they can sometimes evoke beauty.

Ireland: The Irish Wake

The Irish wake provides the template for anyone who would prefer their memorial to be a festive celebration of life.There is revelry amid comfort, and it’s an ecclesiastical catharsis that conveniently combines dancing and mourning. Naturally, drinking plays a huge role in achieving this goal. Attendees swap stories about the deceased over drams of whiskey, often in the same room as the deceased’s body. It’s also customary for mourners to gather at a local pub after the burial service and tell more tales. While modern Irish wakes typically last a day at a remote site like a funeral parlor, traditional wakes would last a couple of days and take place at the home of the deceased or their family members.

Mexico: Dia de los Muertos

Dia de los Muertos, or the Day of the Dead, is a three-day celebration traditionally held between Oct. 31 and Nov. 2. It is not a day of mourning under any circumstances: The annual Mexican celebration stems from an ancient Aztec ritual, and it’s believed that the spirits of the dead are allowed to hang out in the land of the living one day a year. People construct colorful, photo-adorned altars (or ofrendas) festooned with sugar skulls and gifts to joyously welcome back the dearly departed, with a bottle of alcohol close by to provide a symbolic toast. In pre-Columbian times, this liquor was pulque, a funky fermented beverage derived from maguey plant sap. These days, a bottle of tequila or mezcal will do just fine.

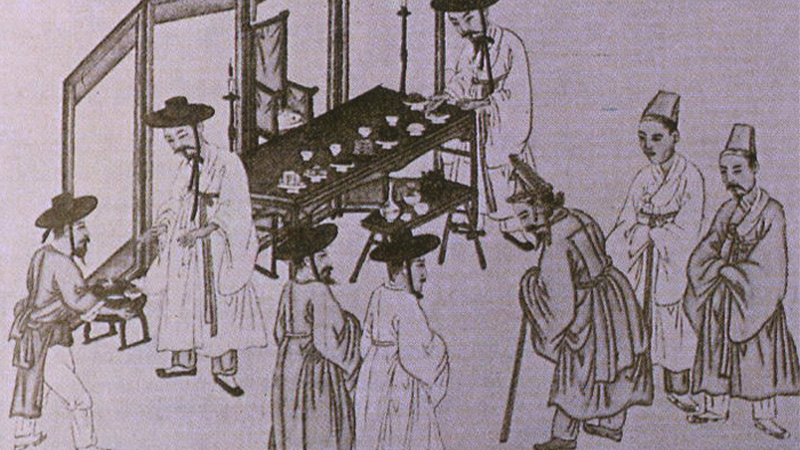

Korea: Sangnye

The Korean funeral tradition of Sangnye blends grief and good times to commemorate the deceased. Alcohol is a key component throughout the process, which traditionally can last a minimum of three days. After friends and family swing by the funeral home to pay their respects, it’s customary to get together and drink into the wee small hours to provide comfort and repel bad fortune. During the procession, pallbearers will stop by a noje, a roadside memorial that attendees adorn with wine, meat, and other offerings to pay final respects and prevent themselves from being haunted by the deceased. After the burial, guests carry out another round of food and wine offerings to help the dead settle in on the other side. Traditional Sangnye are much rarer events these days: Cremations are now more common in Korea, and large feasts typically replace the offering ceremony.

Scandinavia: The Viking Funeral

The ancient Vikings took their alcohol seriously when someone passed. Days-long, post-funeral feasts involving copious amounts of mead and ale were believed to help propel the deceased soul toward the afterlife peacefully. Vikings also turned alcohol into economic leverage through a ritual known as the sjaund: Seven days after a person passed, a “funeral ale” needed to be consumed by the loved one’s family before they could claim their inheritance. While some historical records suggest these rituals sometimes ended in violence, the celebratory aspect of the gatherings remain, and alcohol is still a welcome funeral guest in some Scandinavian countries.

Greece: Pouring One Out

Pouring booze on the ground to honor the dead has been part of common modern vernacular since Tupac Shakur rapped about it in the mid-‘90s. That said, the tradition is far from contemporary. Ritualistic libation-spilling was a bona fide thing throughout ancient civilizations from Egypt to the Israelites. The Greeks fully embraced this ritual by giving it a more modernized spin: Rather than using water, milk, or honey like other cultures, the Greeks preferred to pour out wine to both remember the dead and honor Greek gods and heroes. The ritual was so embedded in Greek culture that it became a recurring motif in Homer’s epic works, the “Iliad” and the “Odyssey.” The Romans would eventually copy this ritual and codify it into their own civilization, as the Romans were wont to do with Greek stuff.

Russia: Vodka and Black Bread

Leaving a single slice of black rye bread on top of a glass of vodka at a person’s gravesite is an important Russian ritual that closes a symbolic and devastating circle. When a new friendship begins, it’s traditional to break black bread to formalize the forging of a new relationship. In these situations, the dense bread can follow vodka shots as a chaser that neutralizes the grain spirit’s strength. The gravesite ritual reverses this concept, as one final gesture that acknowledges the importance the deceased had on the individual. While this ritual was traditionally carried out by the Russian Jewish community, it has been embraced by other pockets of Russian society such as the Russian Orthodox Church. Equal-parts touching and heartbreaking, the practice perfectly highlights how consuming alcohol can bring people together, even when it’s time for death to separate them.