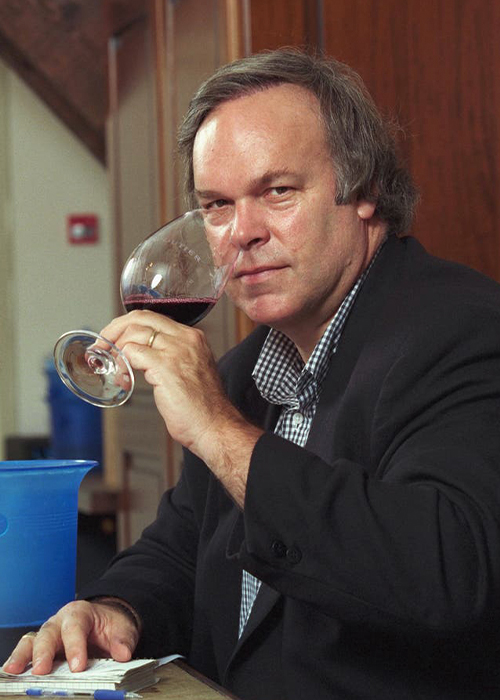

A lot has changed since famed wine critic Robert Parker founded The Wine Advocate over 40 years ago. In the late 1970s, when Parker first began reviewing wines, he was one of the few voices in American wine writing. So when he published the first edition of the Baltimore-Maryland Wine Advocate in 1978, his opinion — one of a law school graduate with no formal wine education — was a welcome one for disenchanted consumers.

1982 was the year Parker truly emerged as the mouthpiece of a wine generation. He was one of the first critics to predict the immense success of that year’s Bordeaux, while others were more critical of the vintage. Years later, in a 2005 Washingtonian interview, he reflected: “I wrote that it was among the best I’d ever tasted and encouraged readers to buy it. Well, it turned out to be a great vintage. Those who bought it really lucked out, or subsequently made a fortune if they resold their 1982s.”

This foresight cemented Parker as the critic to watch in the wine community — especially for wealthy investors — leading to a wide readership of The Wine Advocate around the country, and soon, the world.

Don’t miss a drop!

Get the latest in beer, wine, and cocktail culture sent straight to your inbox.

While his acclaimed palate — famously insured for $1 million — is largely to thank for his success, Parker’s groundbreaking decision to introduce a numerical system to wine reviews is what really set him apart from the pack.

After introducing the 100-point scoring system to his wine reviews, Parker became something of a celebrity in the beverage industry and media, and for a while, his palate became the only one that mattered to collectors as well as winemakers. In an article published in The Atlantic in 2000, William Langewiesche wrote, “When it comes to the great wines — those that drive styles and prices for the entire industry — there is hardly another critic now who counts.”

If Parker scored a wine highly, his readers flocked to wine shops to buy it and soon, winemakers began producing wine with his palate in mind. “There became a formula for certain types of wines,” says Sharon Kazan Harris, founder of Rarecat Wines in Rutherford, Calif. “If you had the right winemaker, the right vineyard manager, and the right kind of flavor profiles, you went straight to being able to access those 100 points.”

The Wine Advocate’s influence grew from an independent direct-mail newsletter to an internationally recognized playbook for wine; Parker’s values became a barometer of success for winemakers; and thus his appetite for big, high-alcohol wines from Bordeaux and Napa broke the levy for an influx of full-bodied reds to the market.

But today, as our wine choices are increasingly swayed by Instagram ads, influencers, and brightly colored labels, how does Parker’s legacy factor in?

The Bigger, the Better

When Parker came along in the late 1970s, the most sought-after fine wines were French. Bordeaux and Burgundy were considered the most high-end regions globally, owed to producers such as Château Canon and Château Cheval Blanc. However, according to Parker’s reviews, Bordeaux’s 1997 to 1999 vintages had yielded overpriced, mediocre wines of uneven ripeness. This resulted in wines that were milder in flavor concentration, a quality that Parker famously critiqued.

When Parker rose to prominence, he turned instead to under-the-radar regions in California, Australia, southern France, and other areas where vineyards experienced much more ripeness of fruit, resulting in intensely flavored, high-alcohol red wines.

“The place where Parker really, truly connected with people was, whether explicit or implicit, he gave them wines that appealed to their fundamental love of ‘more,’” Zach Geballe, “VinePair Podcast” co-host and certified sommelier, says.

“If he gave 100 points, then all of a sudden that wine would sell out,” Kazan Harris adds. At her small-production winery, which emphasizes word-of-mouth marketing, seeking top scores from critics has never been the goal. “I was not going to do a wine that was over-extracted and high-alcohol and very voluptuous in that front palate, which for a while was what you needed in order to get those points,” she says. Though she says Parker’s influence on the wine industry was positive overall, Kazan Harris believes winemakers’ pursuit of high scores led to a misuse of Parker’s reviews. “It became a business instead of this extraordinary tool,” she says.

That’s because, for many winemakers, high praise from Parker was all it took for major success. “One hundred points, and you were f*cking printing the money, from what I understand,” Geballe says.

When Parker anointed the 2010 vintage of Screaming Eagle a perfect score, its price increased by a whopping 46 percent in just six months.

The desire for high scores (and higher price tags) led to an influx of reds that mimicked Parker’s preferred flavors. To this day, many criticize Parker for the sea of sameness hitting shelves: In the aforementioned interview, Parker even admits to having “taken some romanticism out of wine.”

But while many wine pros blame Parker for shifting the American palate toward full-throttle flavors, Geballe believes it may be a case of the chicken or the egg. “It might be almost impossible to say definitively whether he created that taste or merely gave a voice to a wine-drinking public that wanted those flavors, but was not receiving them, especially in the fine wine world,” he says.

Investing in American Wine

Whether or not his success was simply a matter of good timing, there’s no question that Parker’s reviews created an increased interest in American wines. They inspired his wealthy readership to invest time and money into the producers he favored. “He fundamentally created a market in America for collectors of fine wines,” Kazan Harris says.

That’s because, before Parker came along, it was extremely difficult for American wine collectors to decipher the crème de la crème from the mediocre. Unlike French wines, which are marked by longstanding classification systems such as Appellations d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC), Classified Growth Bordeaux, and Premier Cru Burgundies — American wines were free from such pecking orders.

“Wine is intimidating, and one thing that was understandable to the average consumer and/or collector was the authoritative classification systems of certain European appellations,” Geballe says. “What Parker came along and said was, ‘OK, well, we’re going to sort out the wheat from the chaff for you.’”

Parker’s scores became guidelines for investors who could easily spot which wines were worth the spend. Not only is this because his readers trusted Parker to steer them toward quality; it’s also due to the fact that Parker’s highly scored wines were more likely to appreciate over time, making for prized collections. “It definitely gives more surety to the person who’s investing. And more than anything else, it kind of gives everyone in that community a communal shared hierarchy,” Geballe says.

Parker’s Legacy

There’s no question that Robert Parker set up the American wine world for change. Well-off wine consumers suddenly knew which wines would impress their friends and spruce up their wine cellars — often purchasing wines with 90-plus ratings without having tasted them. “And in a lot of cases, not only did it not matter where it was from, but sometimes the more-out-there source of it, the more likely people were to go crazy for it,” Geballe says. “A 98-point wine from someplace in South America that people had never heard of, that was going to fly off the shelves at least as fast as a 98 given to second-growth Bordeaux.”

Put simply, Parker’s reviews put a spotlight on overlooked and underrated varieties and regions, and gave American collectors a better way to categorize fine wines. And though he has since been criticized for reducing wines to a number on his 100-point scale — and for creating a more homogenized market — many winemakers are grateful for his contributions to the industry. “There’s a lot of people who have jumped on the anti-Robert Parker bandwagon. And that’s classic, right?” Kazan Harris says. “Someone gets a lot of acclaim, and then there’s always the anti. I think that I’d love to see a little bit more thankfulness versus the anti.”

Since Parker’s heyday, the way we communicate about, share, and even buy wine has shifted with the times, as social media and heightened globalization increasingly influence the next generation of consumers. Despite this, countless wine shops and even restaurants continue to print Wine Advocate scores on their signs and menus, respectively. Millennials and Gen Zers will still come across the term “Parkerization” when reading about wine, conversing with somms, and listening to podcasts. Their purchasing decisions may even be subliminally influenced by Parker.

While the next generation of wine drinkers may never read Parker’s reviews or factor his scores into their purchasing decisions, “we’re still existing in a paradigm where the generations that Parker connected to — the boomers and Gen X — those folks still have a lot of buying power in the market,” Geballe says. For that reason, at least for now, Parker’s name and legacy remain relevant in the wine community. But with the emergence of online wine clubs, endless wine education resources and opportunities, and the diversification of the wine industry, only time will tell how long that lasts.