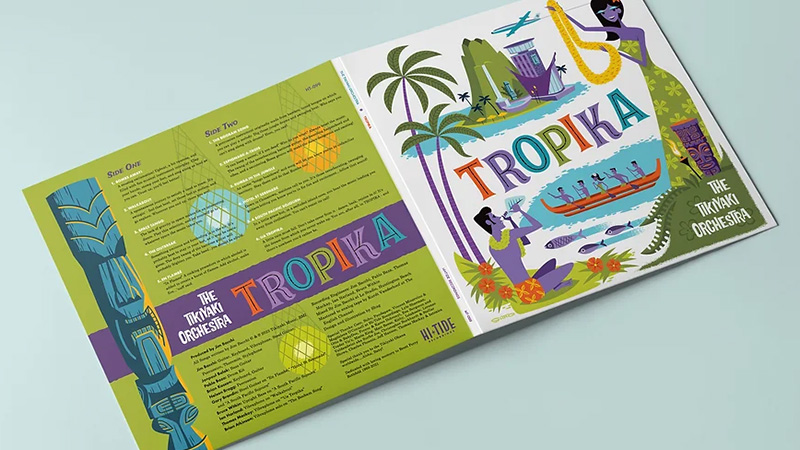

You’re probably not familiar with The Tikiyaki Orchestra. But if you’re a fan of classic tiki bars or modern tropical establishments, you’ve likely heard their music. Or, perhaps more accurately, you’ve felt what their music can help listeners achieve: a sense of far-off serenity.

The instrumentals created by this Los Angeles-based septet of middle-aged dudes tap into a bygone musical style to create soundscapes that bring the zeitgeist of the tiki scene’s mid-century heyday to a modern audience. It’s the music you want to hear with a Painkiller or a Mai-Tai in your hand, largely because it sounds like a Painkiller or a Mai-Tai transcribed to measures and notes: loose, swinging, easy. That’s why selections from their five albums regularly spin at scores of tiki and tropical bars across the country, including some of the circuit’s heavyweights. Tales-nominated hideaways like Sunken Harbor Club in Brooklyn, Strongwater in Anaheim, Calif., and both Phoenix locations of Undertow all fill their spaces with the band’s bewitching sounds. It fits a niche — one that’s about as niche as it gets.

“We’re one of the few groups brave or crazy enough to do original versions of the style of music we do,” explains Jim Bacchi, The Tikiyaki Orchestra’s founder and bandleader. “In fact, when I started the project, I didn’t think I’d find as many people that wanted to play this kind of music as I did.”

The Sound of the Scene’s Rise and Fall

The style The Tikiyaki Orchestra taps into to create their tunes is exotica, a relentlessly retro mélange of surf, lounge, jazz, atomic space race, and spaghetti western. You may have heard songs from the genre, but if you’ve never heard of the genre itself, you’re in the majority. Exotica flourished from the early 1950s to the mid-1960s, an era when legendary venues like Los Angeles’s Tiki-Ti and the soon-to-be-reopened Mai-Kai in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., popped onto the scene as fresh-faced joints. The sound itself was forged from lounge and jazz music, as exotica pioneers like Martin Denny, Arthur Lyman, Les Baxter, and Juan Garcia Esquival expanded upon these genres by incorporating a broader range of instrumental ideas into their compositions. This range included several sounds from the South Pacific and other tropical destinations: Hawaiian steel guitars and vibraharps, Afro-Cuban congas, Indonesian gongs, and jungle sounds like bird calls and the occasional primate shriek.

“That era was the peak of the pop instrumental,” Bacchi explains. “Exotica worked because it drew from so many instrumental ‘food groups’ at the time like surf, jazz, space, and Latin lounge. It created music that was this terrific stew pot of multiple genres.”

As a result, Exotica’s sonic blend evolved to be cool, sleek, and escapist. Its sound naturally evoked the same kind of ambience people sought while sipping on a tropical drink at a bar with a thatched roof or lounging poolside at a lush destination like Hawaii or Palm Springs. This mutual evocation was so strong that some people nicknamed exotica “tiki bar music.”

In the late 1960s, though, exotica music took a nosedive. Pop, rock, and R&B concepts evolved into a progressively serious and exploratory art form, and there was seemingly no room left for exotica’s feel-good instrumental concoctions in the mainstream. The genre’s tumble into obscurity also coincided with the fall of the old-school tiki bar scene, as creators of the style’s classics began taking cocktail specs to their graves and the pre-mixes and shortcuts that defined the disco drink era started to take hold. Some bars survived, but the scene wasn’t the same. Like exotica, it felt as dead as Latin, and only die-hards kept interest.

A Modern Spin on Exotica

Bacchi holds exotica’s trailblazers in high esteem and cites them as an influence. However, he’s quick to credit a ‘90s band called the Blue Hawaiians for sparking his idea for laying down contemporary versions of the style. “The Blue Hawaiians were my gateway band,” he says. “They were creating this fantastic surf exotica music, and it made me want to do that kind of music. However, I wanted to do a hybrid of their style with the styles from the older tiki records of Martin Denny and Arthur Lyman.”

“It was a weird fringe little thing back in 2007, but it’s back to being a bona fide subculture.”

He created the Tikiyaki Orchestra to execute this mission, lifting his old eBay handle for the name’s first half. The second half of the moniker was initially a misnomer — there was initially no orchestra to back him up. “The Tikiyaki Orchestra just started out as just me,” Bacchi explains. “I’m pretty much by myself on that first record [2007’s “Stereoexotique”], with some help on steel guitar.”

Other members eventually joined to justify the complete band name, but the timing of Bacchi’s project wasn’t perfect. The tiki scene was still stagnant when the Tikiyaki Orchestra released “Stereroexotique” and its 2009 follow-up “Swingin’ Sounds of the Jungle Jet Set!” Legendary spots like Tiki-Ti and Trader Vic’s in Emeryville, Calif., were around, of course, but they were more legacy than trendsetter.

Things would be different by the time the band’s third album “Aloha, Baby!” hit shelves in 2011. Renewed interest in tiki and tropical bars began to flourish as the craft cocktail movement started spreading nationwide. This momentum would continue throughout the decade as celebrated bars like Chicago’s Three Dots and a Dash and New Orleans’ Beachbum Berry’s Latitude 29 would open.

“The scene has grown because of craft’s growth,” Bacchi says. “It was a weird fringe little thing back in 2007, but it’s back to being a bona fide subculture.”

Part of the Landscape

As the modern tropical scene continues to thrive and music platforms expand, Bacchi’s need to market his music to bars has waned. “At the very beginning, when I heard of a new bar opening up, I’d call them up and ask them to play our records,” he says. “Now, if a bar goes to Spotify and builds an exotica or tiki playlist, one of our songs will likely show up within the first five selections.”

“We aim to be fun, but not funny. We try to stay true to what the music style is and not do it in a trite way.”

When the songs do show up, they tend to lurk in the background as a supporting player that allows the drinks, décor, and interaction between customer and bartender to take center stage. Bacchi is more than fine with this. “Music is not really the point of a tiki bar unless it’s the wrong kind of music,” he says. “It should provide the backdrop for the vibe. It should set the ambiance. People may not appreciate the music being there, but they will notice if it doesn’t fit.” This doesn’t mean the band resides completely in the shadows. They’ve developed a cult-following over the years, which has paid dividends: They’ve performed live at legendary tiki scene-defining venues Mai-Kai and Trader Vic’s, and they’re a fixture at the multi-day tropical shindig Tiki Oasis in San Diego.

According to Bacchi, one of the secrets to their success is how they approach the genre. While a couple of tracks in their discography satirize the unsavory behaviors of the “Mad Men” era, everything else focuses on paying homage to the exotica genre’s inherent evocation of mid-century cool. “We aim to be fun, but not funny,” Bacchi says. “We try to stay true to what the music style is and not do it in a trite way.” Bacchi also notes this approach is also crucial to the very scene the band supplements musically.

“If you’re going to run a tiki or tropical bar, you must be careful that you don’t play into kitsch,” he says. “You need to be tasteful and respectful about what you’re doing.”

Bacchi doesn’t know exactly how many bars spin the Tikiyaki Orchestra’s music, although he has seen the band’s streaming payouts and royalties increase over the years as more establishments open. Regardless of what the precise number may be, he is satisfied knowing that the throwback tunes played by his band of middle-aged musicians has left an impression within this slice of the cocktail environment.

“If it’s a bar with a tiki or tropical theme, they’ll probably play our stuff,” he says. “It’s comforting to know this, and we’re very grateful that we’ve become so embedded into the scene as much as we have.”