One of the most difficult concepts for new bartenders to grasp is balance. Even if every ingredient in a drink is delicious on its own, when combined in the wrong quantities the finished cocktail can still be undrinkable. The ability to manage the delicate interplay between spirit, sweet, sour, bitter, and dilution separates great bartenders and mixologists from amateurs.

It takes years of deliberate recipe testing to gain anything resembling fluency in this artistic endeavor, and that’s why new bartenders learn to develop recipes using the “Mister Potato Head” method. This approach takes an existing recipe and swaps out one ingredient at a time for one that functions the same but alters the character of a drink — like swapping the simple syrup in a Whiskey Sour for honey syrup to make a Gold Rush, for example.

Countless terrific cocktails at some of the world’s best bars have been invented using the Potato Head template. But eventually, for the forward thinking, these training wheels can become an obstacle in the way of creativity. So what happens when a bar with stellar staff and excellent leadership ditches the training wheels and replaces them with a veritable rocket engine?

Don’t Miss A Drop

Get the latest in beer, wine, and cocktail culture sent straight to your inbox.

Enter: Shinji’s bar, a jewel box located in front of Manhattan’s Michelin Starred omakase temple Noda, devoted to advancing the art and artistry of the cocktail. I sat down with beverage director Jonathan Adler and head bartender Danny Reylock to find out what’s possible with an armory of high-tech tools like chamber vacuums, sonicators, liquid nitrogen, and a full-time pastry chef handling prep. I found a bar that’s having way more fun than you’d expect from its ultra-luxe interior, and one that’s making some seriously delicious and thoughtful drinks. Most of their recipes can’t be executed at home but there are some ideas in play that every thoughtful drinker can — and should — utilize.

Flavorful Solutions to Complex Problems

Adler built the cocktail program at Shinji’s to showcase techniques, but without simply rehashing ideas and concepts borrowed from around the bar world. His background lies in some of the most advanced and exacting fine-dining kitchens in the country — Contra, Saison, and SingleThread among others — and Adler’s distilled those years of culinary creativity and rigid organizational structure into something truly unique.

“I haven’t really read a cookbook or a cocktail book for a long time,” he says. “I don’t necessarily want to be influenced by what other people are doing. I’m not saying that it’s wrong — people do incredible stuff — but I think there’s value in following your own path.”

When designing the opening menu for Shinji’s, it wasn’t about utilizing any specific techniques, but rather a focused pursuit of creating new ones. “For almost every single cocktail, I want[ed] to invent a technique,” he says.

The prime example of this technical ingenuity is the Shinji’s Gin Fizz. The bar’s version of the classic Ramos includes powdered, liquid-nitrogen-flash-frozen whipped cream, and cuts the usual minutes-long shake down to about 10 seconds. It took almost a full year of tinkering to get to the final spec, but that R&D led to a perennial menu favorite and an infectious culture of curiosity among the staff. Head bartender Reylock outlines how the staff has learned to keep asking questions and keep pursuing the next delicious cocktail: “How can we make a Dirty Martini with no olive brine? How can we use an entire fruit in a cocktail? That’s where I think we have the space to grow.”

This curiosity led to a fascinating through line across the menu at Shinji’s. The bar uses very few traditional modifiers in any of its drinks, because Adler didn’t want to be stuck with only the products that are already in a bottle on a shelf. The issue, he explains, is that when using an existing product, you’re bound to the alcohol, sugar, and water content in the bottle. “You are forced to work the rest of your cocktail template around that,” he says.

So Adler found a more elegant solution: When there wasn’t a product available on the market that fit his exacting vision for a cocktail, the team simply made their own. Some of these are more complex than others. For the “Honeypenny,” a cheeky Vesper variation, Adler didn’t want to use the Lillet Blanc that’s on the market today because it’s decidedly less bitter than the original wine-based Quina Lillet modifier of yesteryear. Rather than settle or substitute, Adler turned the drink on its head. Vodka became both the bittering agent and sweetener after an infusion with cinchona bark and golden raisin, the addition of honey, and a fat wash with beeswax for mouthfeel.

Why alter the spirit and not just beef up an existing modifier? The vodka, at 40 percent ABV, “is going to be very good at extracting flavors because alcohol is a solvent, and at a higher proof, it’s going to extract more flavor,” Adler explains. The cocktail is now sweetened and bittered, and more floral complexities can be introduced to the finished drink via gin and — the secret weapon — a bone-dry mead from Bushwick’s Enlightenment Wines. The team took every opportunity to add flavor and cranked the dial to 11.

From Spirit to Liqueur

The majority of the ingredients at Shinji’s lean on the prep wizardry of “Batch Queen” and executive pastry chef Charmaine McFarlane, who takes these complex recipes and scales them for service. Others are suitable for any bar — no nitrogen or ultrasonic homogenization required.

One such ingredient involves taking a spirit and turning it into a liqueur with the simple addition of sugar and some time in a blender. For “The Last Word, I Suppose,” Adler sought to replace the oft-maligned Luxardo Maraschino in a traditional Last Word. He turned to Empirical Spirits’ The Plum, I Suppose, a distillate made from citrus marigold kombucha and plum kernels. Empirical represents a new class of producers completely bucking traditional “rules” around spirit classification. The company’s focus is vacuum distillation with bold flavors and uncommon grains. (Tough to explain to first-time drinkers, but delicious in a cocktail.) To Adler, The Plum, I Suppose mimicked the baking spice and stone fruit notes he enjoys in Luxardo without the cloying, medicinal qualities. The two products are also bottled at the same ABV — the Empirical just lacked the necessary sweetness to swap in Potato Head style.

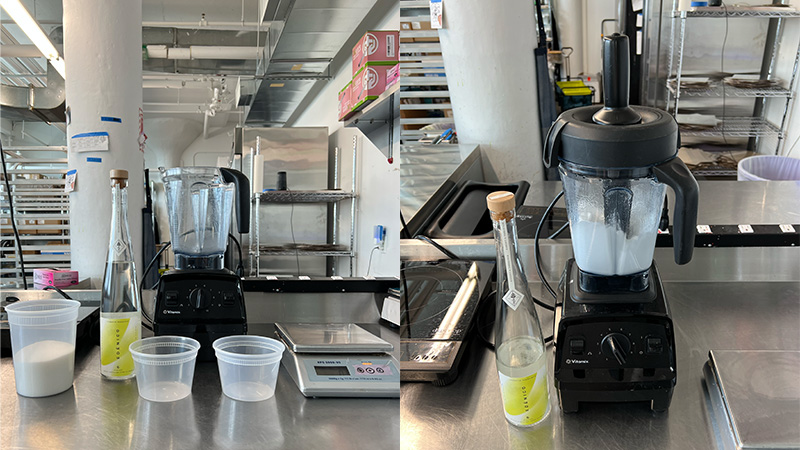

It took a few rounds of pointed R&D to settle on the right quantity of sugar to achieve the sweetness of the Luxardo Maraschino. Adler eventually settled on 25 percent of the weight of the spirit in white sugar**. The process is remarkably simple, with sugar and Empirical added to a blender and blitzed on medium speed for a few minutes to combine without heating. This sweetened spirit/liqueur can live happily in a bottle at room temp, and be used like any other liqueur.

Of course, because the Luxardo and Empirical products have the same 32 percent ABV starting point, some back-of-the-napkin math tells us that a 25 percent addition in sugar by weight would increase the volume of that product roughly 15.75 percent, while leaving the total alcohol quantity unchanged. The ABV of the new Empirical liqueur is therefore now a noticeably lower 27.6 percent. Adler anticipated this change, and adjusted the spec of his Last Word accordingly, bumping up the quantity of gin from three-quarters of an ounce to a full ounce.

While discussing the drink with Adler in one of Shinji’s booths, Reylock swung over with the bar’s ever-so-swanky tableside drink cart and shook one up. It was the most delicious Last Word I have ever had the pleasure of tasting. With hard evidence proving that the technique was absolutely worth exploring, I dug deeper into the philosophy behind it: Why not simply add the Empirical along with a measure of simple syrup to the drink instead of making the liqueur?

For Adler, it’s all about concentrating flavor and controlling dilution. The water in simple syrup is unflavored, and therefore increases overall sweetness but dilutes the flavor. Of course, the drink will get diluted when it’s stirred or shaken with ice, but this technique gives the Shinji’s team that extra degree of control that they believe yields the most delicious cocktail possible.

This exacting philosophy bleeds into every aspect of service at Shinji’s from hospitality to staff education. “We always want to have these amazing standards, then we can push the envelope,” Reylock says.

I decided to take this blender technique for a spin to see if I could “fix” another classic that I just can’t bring myself to love — also for Maraschino reasons: the Martinez. I was inspired by the Shinji’s drink to go spiced- and fruit-driven, so I reached for a bottle I was recently introduced to and immediately smitten by: #5 Plantain Eau de Vie from Mexico’s Edenico. It’s phenomenal neat in a glass — rich with estery green banana notes — but with a touch of sweetness the eau de vie was transformed into pure bananas foster. It was ridiculously simple to turn into a liqueur, I just followed that same 25-percent-by-weight guideline and tossed it in a blender.

I sincerely hope you’ll try sweetening spirits at home and come up with something unique and delicious!

Plantain Liqueur Recipe

Ingredients

- 200 grams Edenico #5

- 50 grams sugar

Directions

- Add ingredients a blender.

- Blend on medium speed for up to 5 minutes, or until all sugar is dissolved and emulsified.

For the final cocktail, I wanted to keep leaning tropical, so I landed on Mattei Cap Corse Blanc for my vermouth, and the lovely vacuum-distilled Crazy Gin — a new gin out of London that utilizes all the flavors of classic Indian lassi, including yogurt, pomegranate, and ghee — to give the drink a voluptuous mouthfeel. The drink certainly strayed far from the classic Martinez, but retained its soul in new vibrant attire.

Martinez #5 Recipe

Ingredients

- 2 ounces Crazy Gin

- ¾ ounce Mattei Cap Corse Blanc

- ¼ ounce Plantain Liqueur

Directions

- Add all ingredients to a mixing glass.

- Add ice and stir until chilled and diluted.

- Strain into a chilled coupe and garnish with a grapefruit twist.

**I can already hear the refrain from tech-savvy bartenders in the back of the auditorium: “Why can’t you just measure the Brix (percent sugar by weight dissolved in a solution) of both products on a refractometer and add sugar until they match?” If we were talking about alcohol-free, clear solutions like syrups, that would absolutely be a valid methodology. But a neutral spirit with no sugar in it also refracts light, so it will give you a non-zero reading on a refractometer. Additionally, that reading will change in a non-linear fashion depending on the ABV of the spirit. It can even be affected by ambient conditions like the temperature of the liquid itself. If you attempt to measure the sweetness in Brix of a product containing both sugar and alcohol on a refractometer it will only lead to heartache. It’s like trying to use balsa wood and glue to build a space shuttle — it might get you somewhere but definitely not the intended destination.

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!