When Jedd Haas started his distillery Atelier Vie in New Orleans in the early aughts, rice whiskey wasn’t in the plan. But with other distillers already making Louisiana sugar cane rum, he wanted a way to stand out. “I had heard about various types of rice spirits made in Asia and thought, ‘Let those guys make rum; I’m going to make some rice whiskey,’” he recalls. Now, Atelier Vie’s annual release of Riz Louisiana Rice Whiskey sells out.

Haas is one of a small number of distillers who are crafting a contemporary image of what the world’s third most abundant cereal crop can offer. Rice has long been used in making spirits in Asia, from shochu and sake to baijiu and lao-lao, but it’s been largely absent in U.S. distillation until recently, as distillers look to expand the whiskey spectrum or connect with their Asian beverage heritage and culture.

Rice Whiskey’s Asian Heritage

The growing interest is also partly due to imported Japanese rice whiskies. Small distillers including Kikori, Ohishi, and Fukano offer various expressions in the U.S., and even giant Suntory has joined in with its experimental Essence of Suntory series.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning Daily Dispatch newsletter—delivered to your inbox every week.

According to producers, rice whiskies can be soft and light when fresh, but they evolve quickly in barrels and have the potential to attract whiskey novices and, with more elaborate aging methods, the connoisseur.

“Rice makes a very malleable spirit,” says Chris Uhde, the vice president of importer Impex Beverages, which imports two rice whiskies. “It comes off the still pretty soft and takes on the characteristics of the barrel in a positive manner. With rice whiskey, it’s usually after about 12 months that it gets this really nice balance, and the longer it sits, the more intensified it becomes.”

Uhde says different types of rice and barrels are beginning to define American versions. “Smaller new barrels give a heavy oak influence that dominates with a light-mid-palate.” The brands his company imports—Ohishi and Fukano—age in a range of larger used casks for longer periods. Ohishi uses five types of rice, distilling and aging them individually and then blending. Fukano combines malted and un-malted rice in a pot still and bottles only a few casks each year; both distillers will age their spirits 10 years or longer.

Owner Ann Soh Woods created Kikori Whiskey to be “a smooth, drinkable spirit” for personal enjoyment. “What it became was an ode to the thoughtful traditions of Japan which inspires moments of cultural discovery in others,” she explains. Made on the southern Japanese island Kumamoto with locally grown rice, Kikori is aged at least three years in American and French limousin oak and sherry casks, creating what Woods calls roundness and depth that could appeal to light and dark spirit drinkers.

Perfecting the Technique

Japan has a heritage of rice distillation that American novices lack. “The challenge of distilling rice is you have to cook it to a pretty high temperature for some time and find the proper enzyme regime to convert the starch to sugar,” says Haas. “When I first started making it I thought, ‘Can you really make whiskey out of this?’ Theoretically, I knew it could work, but I didn’t know how, or how it would taste.”

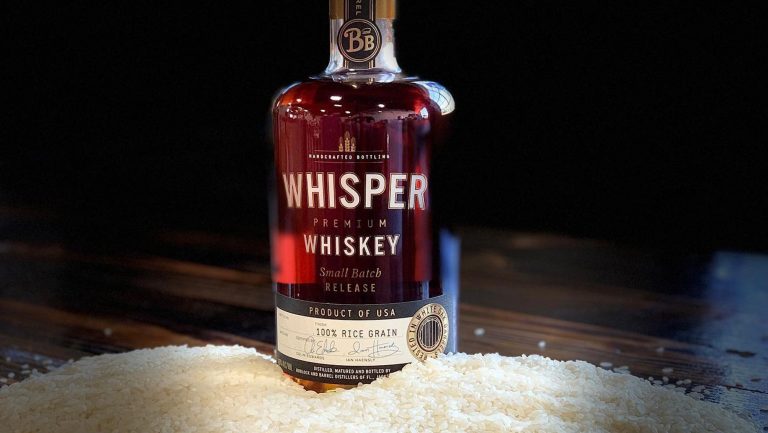

Colin Edwards and Ian Haensly, cofounders of Jacksonville, Florida’s Burlock and Barrel, have been selling out their Whisper Rice whiskey, although getting it right was time-consuming.

“Rice takes a 24- to 30-day fermentation,” says Haensly. “It’s tough to break it down to get it to the point where it’s worth making.”

“It’s the only grain where you have dual-saccharification,” says Edwards. “You have to convert starch to sugar and sugar to alcohol at the same time.” While Asian distillers spark fermentation with the koji mold, Edwards and Haensly settled on yeast and a non-koji spore.

Problems aside, the results have satisfied makers, though most batches have been modest. The first Riz was unaged, but Hass prefers to bottle a three-year-old from a mix of 53-, 25-, and 5-gallon used barrels.

Embracing Heritage and Pushing Boundaries

It was a combination of serendipity and history that brought the Ly family into whiskey.

“We’ve been making rice spirits for seven generations,” says Michelle Ly, who co-owns Vinn Distillery with her siblings and parents in Wilsonville, Oregon. Her sister Lien Ly, the distiller, found some small barrels at a garage sale and filled them with baiju. “We tasted it and were really surprised. We asked, ‘Can we call this a whiskey?’ We looked it up and confirmed that we could as long as it’s grain-based and it touches oak, and that’s how our whiskey came about.”

Now it’s a top seller although at the sampling room, and they don’t tell customers it’s rice-based. “They know it’s not typical rye or wheat or corn, but they can’t quite pinpoint what it is,” says Ly.

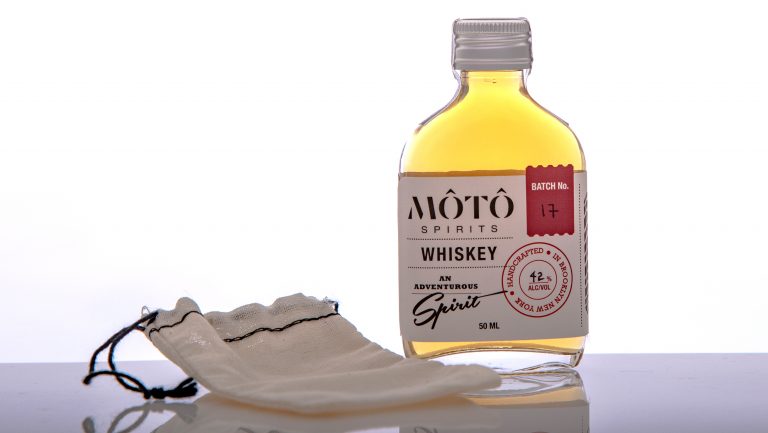

The creation of the Brooklyn-based Môtô was even more whimsical.

Marie Estrada’s co-owner Hagai Yardeny returned from Vietnam in 2016 with a strong rice wine she hated, but both wanted to try making their own. After months using rice cookers and leased spaces, trying new barrels that left the spirit tasting “like sawdust,” they settled on a Japanese-style rice from California, ex-bourbon barrels, and single barrel spirits packaged in 200-milliliter bottles they self-distribute.

“We have to overcome the language of whiskey when we’re telling people this is rice-based,” she says. “It resembles a rye whiskey with softer notes.”

Estrada thinks there’s potential for a growing market especially if the trend for gluten-free continues. “I think the market is just excited for something different,” she says. “There’s a lot of room for innovation.”

Uhde agress. “Because of how well the rice lends itself to be manipulated by the barrels, it’s a wide-open category. So you can go into it and expect almost anything.”

Jack Robertiello, from Brooklyn, New York, has worked in and written about the world of drinking and eating for most of his adult life. He speaks frequently at conferences and judges competitions, and works in the industry as both a teacher and consultant.