The young, fast-growing American single malt whiskey category is now at a crossroads.

For the past two decades, the curiosity factor surrounding American single malt buoyed producers as they ramped up production and fine-tuned the skill of distilling malted barley.

While American single malt distillers produce a fraction of the volume of their Scottish counterparts, there are now 170 single malt distilleries in production in the U.S., more than in Scotland, which has 120. As the category has matured, producers face new challenges: most importantly, the need to establish a point of differentiation in an increasingly crowded category and how the distilleries should operate in a legally amorphous category that lacks consistent regulation.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning Daily Dispatch newsletter—delivered to your inbox every week.

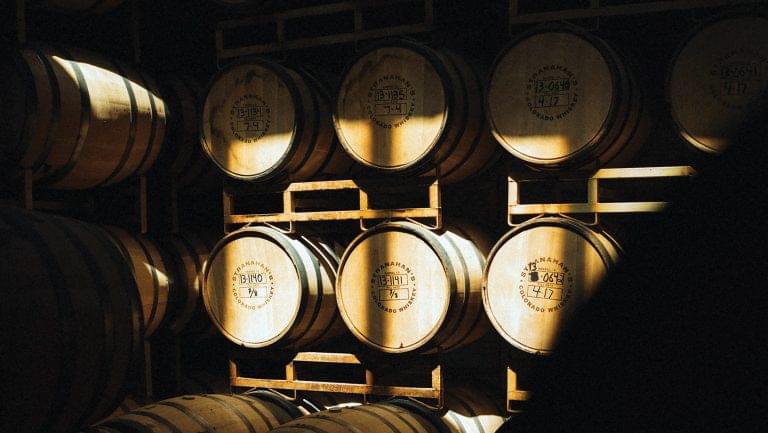

With predominantly identical mash bills of 100 percent malted barley, what remains to separate one whiskey from another lies primarily in aging choices, production tweaks, and regional climate. For example, evaporation rates—the volume and speed of liquid lost, otherwise known as the angel’s share—vary dramatically among Westland Distillery in rainy Seattle, Balcones in sultry Waco, Texas, and Stranahan’s in mile-high Denver.

Westland has leaned on regionality to stand out, making barrels from the Pacific Northwest’s native garryana oak to create single malt whiskeys that showcase what master distiller Matt Hofmann calls the wood’s uniquely dark and deeply flavorful impact. Westland also highlights its Pacific Northwest identity by aging whiskey in barrels from local beer, wine, and spirits producers.

Westland certainly isn’t alone in exploring wood influence. The production team at Virginia Distillery Co., in Lovingston, uses casks formerly used to age Sherries (Amontillado, Fino, Oloroso, and Pedro Ximenez), Moscatel, Madeira, Calvados, and cider. Single malt specialist Westward Whiskey, in Portland, Oregon, recently released a limited edition Sourdough whiskey, and it’s also had success with Stout Cask and Pinot Noir Cask limited editions.

At Virginia Distillery, the recipe for single malt whiskey is an evolving one that yields new insights all the time, says CEO Gareth Moore: “We laid down some whiskey in ex-apple brandy casks in 2015, and nothing really happened. With the cider cask finish, I thought we may have produced more than we could sell, but then we got an award and our distributor ran out the same day. It’s very hard to know what will work.”

Although a used barrel’s provenance is often crucial for a producer, many American single malt distillers are willing to leave more to chance. For whiskey that Westland’s Hofmann ages in ex-beer barrels, “The key is to allow the breweries to produce what they want and then go with the flow,” he says. He cites casks that made the trip back and forth between Westland and Black Raven Brewing in Redmond, Washington, where they’d been used to aged sour cherry kriek and coffee stout. “We initially thought to do two releases, but found that blending them together yielded a much better whiskey, and to us, that’s where innovation comes from—to work within the confines of what we get back,” he explains.

Allowing Terroir to Shine

American single malts are often criticized for an overabundance of fresh oak, but some distillers, including Virginia Distillery (which just released its first single malt, Courage and Conviction) and San Jose’s 10th Street, have opted for shaved, toasted, and recharred casks (known as STR); it’s a cask preparation method pioneered by the late whiskey consultant Jim Swan, Ph.D.

“The STR casks let us increase the wood element but without overpowering the malt,” says 10th Street CEO Virag Saksena. “Malt is milder and more nuanced than corn and rye, which can stand up to fresh wood, although even then you need to wait for that initial harshness to disappear. You put malt in freshly charred casks, what you taste is mostly wood.”

Dialing back on oak allows regional character to emerge. At Balcones in Texas, head distiller Jared Himstedt conducts endless experiments to achieve greater terroir expression, starting with using barley grown and malted in Texas. “Exploring the climate and how that affects maturation, along with local microflora entering and participating in the fermentation, means we are really making whiskey that can only be made here,” says Himstedt. “Everything is on the table, from entry proof and cask sizes to yeast strains, pitching rates, and final mash pH.”

The Push to Define the Category

Up to now, the industry has been built on creativity and freedom to try new things. Looking ahead, there’s an industry-wide agreement that the regulations governing the American single malt category need to be established. Producers are faced with perplexing Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) rulings: Some have been allowed to put “American single malt whiskey” on one line on labels, while others are not, and some can age their single malts in used oak barrels, while others are not permitted to do so. Creating a uniform set of official standards for the American single malt category would create consistency and transparency, say proponents.

The 170-distiller member American Single Malt Whiskey Commission (ASMWC) first sent a proposal to the TTB for an official category definition in 2017, but the organization is still waiting for approval. With few exceptions, American single malt makers hew to familiar Scotch-Irish rules—100 percent malted barley distilled and bottled in one U.S. location—so the ASMWC-proposed definition includes those regulations, plus the following standards: a maximum distillation proof (80 percent ABV) and minimum bottling proof (40 percent ABV).

However, several proposed rules have raised some eyebrows. First, there’s a requirement that would mandate a maximum (700 liters)—but no minimum—oak barrel size, which concerns pioneer Lance Winters of St. George Spirits in Alameda, California, one of the first U.S. distillers to lay down single malt two decades ago.

“There’s an awful lot of reliance on new wood to the point that so many American whiskeys taste like you’re licking a saw mill,” says the self-described “grumpy old man on the porch.” Winters explains that allowing larger barrels and limiting barrel size to no smaller than 53 gallons would make more sense: “Over-extraction will ruin the category more than large barrels will.”

Another concern with the proposed rules is the lack of a proposed minimum age. A distiller could fill a barrel and empty it 15 minutes later and bottle the whiskey as an American single malt. Of course, bourbon and rye makers can do that, too, but they rarely do. Yet with the intense pressure for young distillers to develop cash flow, it’s possible that some might try uncommonly fast time in barrel and damage the category’s quality image.

Other rule tweaks might be useful as well. According to Owen Martin, head distiller at Stranahan’s, which is about to release the 10-year-old Mountain Angel, a whiskey’s age is not permitted to take into account the time spent in finishing barrels. “Stranahan’s Sherry Cask is considered a four-year-old because it ages for four years in new American oak barrels before being transferred into Oloroso Sherry barrels. The time in the finishing barrel can’t be taken into account for age statements,” Martin notes, adding that he thinks American rules should allow what Scotland does not in terms of finishing aging.

Matters of Taste

Whatever the TTB ultimately decides, Steve Hawley, ASMWC president and global marketing director for Westland, says that the purpose of the proposed rules is not to set barriers. Instead, they would establish U.S. producers within the world’s understanding of what single malt is.

“We don’t want to be the arbiters of taste of single malt,” Hawley says. “We see our role as defining the parameters but not going so far that they start to regulate taste. In our minds, what we’re trying to do is relatively obvious and straightforward, addressing a definition specific enough to mean something but also leaving room enough for innovation.”

Certification would also strengthen producers’ attempts to establish dedicated shelf space at retail, say proponents. However, producers such as Winters, who says his Lot series of St. George wouldn’t qualify under new rules while his Baller label would, will still need to continuously educate consumers.

And some distillers are content to work outside the proposed rules as they use malt differently: Woodford Reserve, which released a 100 percent malt whiskey at the turn of the century, found that a straight malt with 51 percent malt, 47 percent corn, and three percent rye mash bill produced a whiskey more to their consumer base’s liking, says distiller Chris Morris. Woodford calls it a Kentucky straight malt whiskey.

Above all, says Himstedt, is the idea of transparency, “and empowering the consumer to understand what they’re buying. With an aligned standard of identity, we can establish some guardrails that will ensure the health of the category moving forward while educating and protecting consumers.”

It may take some time for the notoriously overworked and slow-moving TTB to create standards. But, says Hawley, “We should be practiced at being patient; we make whiskey for a living.”

Jack Robertiello, from Brooklyn, New York, has worked in and written about the world of drinking and eating for most of his adult life. He speaks frequently at conferences and judges competitions, and works in the industry as both a teacher and consultant.