This feature is part of our 2023 Next Wave Awards.

This fall, The Long Island Bar will mark a decade in business under the stewardship of co-owners Toby Cecchini and Joel Tompkins. But there will be no party or special menu to celebrate the occasion.

You’ll understand if Cecchini is a bit superstitious about acknowledging such milestones. His first bar, Passerby, in New York’s Meatpacking District, was a year shy of its 10th anniversary when he lost the lease due to a demolition clause. He and Tompkins thought they could find a space to open a new bar together within six months, but the search would take six years. It proved to be worth the wait.

Don’t Miss A Drop

Get the latest in beer, wine, and cocktail culture sent straight to your inbox.

Ramon Montero opened The Long Island Restaurant in 1949 (or 1951, by some accounts) on the corner of Atlantic Avenue and Henry Street in Cobble Hill, just a few blocks from the Brooklyn waterfront. Montero’s daughter Emma and her husband Buddy Sullivan were the caretakers for nearly 60 years with the help of Emma’s cousins, Maruja and Pepita (Cecchini lovingly refers to Emma and her cousins as the “Three Graces” and celebrates their legacy with three small plaques with their names at the end of the bar).

After Buddy died in the mid-’70s, Emma and the cousins kept things running until one day in 2007 a “closed” sign went up, leaving the future of the historic space uncertain.

Tompkins and Cecchini were among the many restaurateurs and bar owners who wondered about the possibilities this vacant ghost ship might hold. “I had spent so many times walking by there and staring in through the papered-up windows and thinking, ‘Holy sh*t, what we could do with such a space,’” Tompkins recalls. And as fate would have it, through a serendipitous encounter with Emma, they signed the lease in 2011. After two years, they had restored the mid-century Art Deco venue to its former glory while honoring its past — varnishing over (but keeping) the many cigarette burns that scarred the bartop and restoring the iconic pink and green neon sign, which hadn’t worked since the 1970s.

“I have a photo of Buddy Sullivan, the original owner who ran this place, that hangs in my office,” Cecchini says. “Our sort of joke is, WWBD (What Would Buddy Do?). I see myself as a sort of cog in the history of this place.”

Though the “Ocean’s 11”-like team of veteran bartenders will stir up most anything guests desire, the cocktail list at The Long Island Bar is a relatively tight lineup of originals and revised classics like the A Martini (Hepple Gin, Dassai 50 Junmai Daiginjo Sake, Lustau Blanco Vermut, bergamot-pomelo tincture), The Long Island Gimlet (made with housemade lime-ginger cordial), a perfect Boulevardier, and the White Negroni Sbagliato. It’s also common to see countless baskets of fried cheese curds and orders of L.I. burgers and fries flying out of the kitchen.

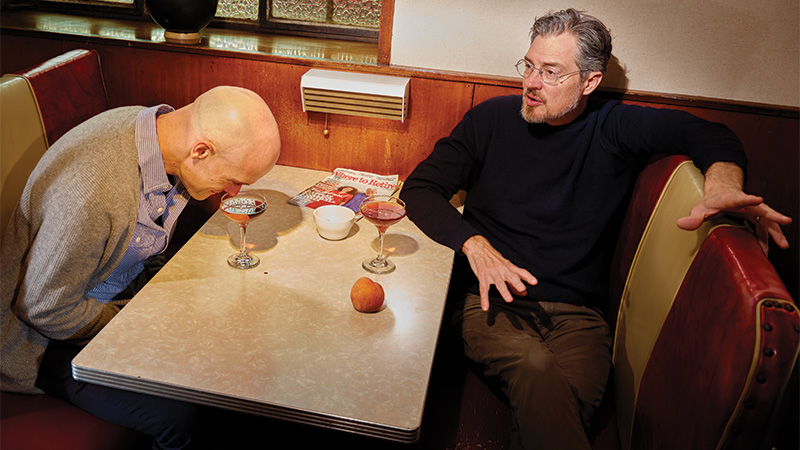

“It’s a magical room. You can see it on almost everyone’s face the first time they walk in. It’s the kind of place you want to hang out in,” Tompkins says. “And the fact that you have these top-notch bartenders sort of casually putting out excellence without a whole lot of fuss, and food that we like to think is better than you’d expect in a room like this. It all adds up.”

Even so, it’s hard to put a finger on just one thing that makes the bar such a special place — one that has fostered a community of regulars and draws crowds of guests from the neighborhood and beyond every evening.

“When you walk into a really well-run place, it doesn’t have to be highly polished, but you notice little clever things where you can tell there are people taking care of this place. You sort of see the wheels turning,” Cecchini says. “That’s what I would hope happens when you walk in here.

It’s a neighborhood tavern and I fully embrace that. I don’t want it to be anything more than that, actually.”

As for the bar’s icon status, drinks historian, writer, and bar regular David Wondrich says: “At a time when so much of Brooklyn’s past is being torn down or thrown in dumpsters, they kept a really strong link to the weird, not fancy steel town on the river that Brooklyn was for most of the 20th century. For that I’m grateful. I’m grateful for the grownup-ness of the place; the refusal to pander or chase trends. I think — I hope — that their legacy will be like Harry’s New York Bar’s legacy: a bar’s bar and an oasis that never runs dry.”