At 50 years old, Tom Maas was already financially secure and had essentially retired. Then boredom set in. He could only play so many rounds of golf, only go to so many Thursday afternoon Cubs games by himself. He needed a new venture to occupy his days. Why not create his own booze brand?

After a lifetime in the liquor business, starting in the late 1970s which saw him work on the executive level for three of the biggest whiskey brands in the world — Jack Daniel’s, Canadian Club, and, toward the end, as director of bourbon worldwide for Jim Beam — he felt he knew product development pretty well, and thought the agave world was actually where all the unexplored opportunities were. Namely, in the making of a tequila steeped with sweet and hot peppers — perfect for use in the spicy Margaritas that were becoming zeitgeisty. Launched in 2005, Agave Loco was an instant hit, and Maas started thinking more about this often-unexplored Latino customer base.

“In one of my final roles with Beam, we had started to do focus groups with people of Hispanic descent to see if we could move them into the bourbon category,” recalls Maas. “At many of the groups, respondents sometimes made jokes that if you mixed Jim Beam with horchata every one would drink it.”

Don’t miss a drop!

Get the latest in beer, wine, and cocktail culture sent straight to your inbox.

At the time, Maas wasn’t even aware of what horchata was, though he always kept the name in the back of his mind. One day, around 2006, thinking about more products he could launch, Maas asked his youngest son, Nick, if he knew what horchata was.

“He took me to a burrito shop and I tried the non-alcoholic version,” says Maas, referring to the plant-based milk beverage, often flavored with sugar, vanilla, and cinnamon, that has long been a popular homemade treat in many Latin American homes. (It is sometimes said to be the second most consumed beverage in Mexico after water.) “I felt the flavor was fantastic and would make a great liqueur,” Maas says.

He quickly began sampling horchatas from all of Chicago’s taco stands and burrito shops and eventually found a style he liked. He began test-batching his own horchata recipes in his kitchen at home and then began experimenting with different alcohol bases. Rum stood out due to its inherent flavor profile, which Maas thought complemented the vanilla and cinnamon typically added to horchata. Conveniently, Maas’s father, Duane, a renowned distilling engineer, was then consulting for the West Indies Rum Distillery in Barbados and helped him source some custom-made light rum.

Maas, meanwhile, was beginning to realize he might not want to use jicaro seeds or rice water for his base, as was traditional in horchata. Especially as he already had a strong knowledge of dairy-based liqueurs from his days working on the Starbucks Cream Liqueur for Jim Beam.

“Real horchata is not made with dairy — I made it with a dairy base so that it would have a more luxurious appeal,” says Maas. It would also allow him to charge a bit more.

After two years of tweaking flavor profiles and building his own bottling facility just outside of Milwaukee — which would be run by his then-81-year-old father — this crazy concoction was ready for retail. By then, Maas’s business partner and package designer, Pete DiDonato, had already taken the liberty of trademarking the name RumChata.

“To this day, though, the vast majority of people who drink RumChata do not know what horchata is,” claims Maas.

Cinnamon Toast Crunched

Maas’s initial plan was to sell RumChata to Mexican restaurants as an after-dinner dessert drink. But that idea didn’t really pan out. With unimpressive sales, it was clear that the diners in question had little to no interest in mixing horchata with alcohol. So much for those Jim Beam focus groups.

“I was in a quandary as to who would drink the product if it was rejected by the Hispanic consumer,” Mass recalls.

Needing to start making some money ASAP, Maas’s only real option was to present the few bottles he did have to his ample contacts at bars and restaurants throughout the Midwest. While he found unexpected luck early on at a biker bar, it was 20-somethings who quickly latched onto RumChata, with many telling Maas it reminded them of the milk left over after eating a bowl of Cinnamon Toast Crunch.

Maas had never had the General Mills cereal before, but, after buying a box, found it hard to disagree with their assessments. Instead of rejecting such a childish comparison, he quickly pivoted and began leaning into that similarity, purchasing thousands of single serving “bowlpaks” of Cinnamon Toast Crunch off Amazon and giving them out as a bar promotion.

Soon, bars were serving shots dubbed the Cinnamon Toast Crunch, a mixture of the 12.5 percent ABV RumChata proofed higher with the addition of Fireball, another liqueur becoming red hot at the time. (Maas claims it was the state’s overall most popular shot from 2011 until 2015 or so.) By the end of that first year, Maas had moved 20,000 cases of RumChata. It was slowly building in the Midwest, even if the coasts had yet to really hear about it.

“There are so many different palate interests ranging throughout the country,” says Brian Bartels, author of “The United States of Cocktails.” For over a decade he served as beverage director for New York City’s Happy Cooking Hospitality, before returning home to Madison, Wis., to open Settle Down Tavern in 2020, where he finally encountered the state’s passion for RumChata and its ubiquity on back bars. “RumChata is definitely an underground sensation [in Wisconsin] to say the least,” Bartels says.

Back in 2010, however, America was still in the tail end of the subprime mortgage crisis. So success was a bit of a double-edged sword for Maas. He couldn’t get any major banks to lend him money to fulfill things like a million-dollar purchase order from Southern Glazer’s, America’s largest spirits distributor. At one point, Maas had no choice, as he recalls, but to put $220,000 worth of glass bottles across multiple credit cards. And yet, he had such belief in the product, he wasn’t all too stressed.

“By the time I was this far into it,” says Maas, “the Tarot cards were all coming up positive.”

And they were finally flipped over one day in late 2011, when he walked into Woodman’s, a Midwestern supermarket chain, and was greeted with a hand-scrawled sign on the door reading:

“LIMIT: one bottle of RumChata per customer.”

Like Chocolate Cake After Steak

By now Maas was starting to get offers from money men as well, “vulture” capitalists as he calls them, who presented him with deals he thought to be worth 20 cents on the dollar. At one meeting with a VC firm, he recalls being presented with a check for $25 million dollars, which he promptly turned down.

“My father was kicking me under the table,” recalls Mass. “But I knew we had bigger opportunities there.”

By the time Duane Maas died a few years later in 2016, RumChata had become the second best-selling cream liqueur in the nation, just behind Baileys Irish Cream, moving over half a million cases per year. By some accounts, it was the No. 1 liquor brand on social media, too. It certainly helped that, by the late-2010s, “horchata” was one of those ambiguous flavor profiles — like salted caramel or pumpkin spice — that had just become trendy.

As of 2019, RumChata was distributed to every state in the union, plus a couple of international markets. Maas thought they had the ability to get to 1 million cases per year, to begin getting that virality in other places that he had fully obtained in the Midwest, but he knew he wouldn’t be able to handle such a big job by himself. The pandemic only sped up his desire to unload RumChata.

“Covid really, really scared me,” says Maas. He had 80 employees, and was stressed about what might happen to all those families if he made a bad decision and things went south. “It wasn’t hard to sell it after thinking about that.”

With so many suitors, he went with an offer from E&J Gallo, liking that they were a family operation (Duane, in fact, had once done business with Ernest J. Gallo, the family patriarch) and that they wished to acquire his bottling plant as well, retaining all 40 employees who worked there. All the ingredients have remained the same, though, amusingly, it’s become harder to source milk these days than rum.

“When the opportunity presented itself [to acquire the brand], it was certainly something that caught our attention and picked up speed quickly,” says Brandon Lieb, the vice president of spirits marketing for Gallo. “Originally being a Midwesterner [from Green Bay, Wis.] I already had a lot of exposure to RumChata from trips back home, and was well aware of its possibilities.”

One of the problems — though it seems to be a good problem to have — is that even Gallo isn’t quite sure how to best sell RumChata. It remains wildly popular as a shot. It’s also evolved to be popular in frat-tastic “bomb”-type drinks. (“That is certainly something that has happened organically,” Lieb notes.) It’s finally getting a little push with Mexican-Americans, and it does great at the kinds of family-friendly chain restaurants that have long had a history of serving decadent, Mudslide-type drinks. Bartels, for one, believes it is a serious asset in hot toddies.

“Being in Wisconsin, one is privy to some cooler winter months,” he explains, “and with Covid forcing us to be creative with indoor/outdoor options for our guests, I experienced something never before last fall and winter: the ravenous hot toddy drinker.”

His bar now offers a full hot toddy menu, and two of those cocktails involve RumChata. The “October 4th, 1950” deploys two ingredients Bartels had never used in New York bars: RumChata and Skrewball Peanut Butter Whiskey, while the “Cinnamon Smoke Crunch” matches RumChata with mezcal and Allen’s Coffee Brandy. For its part, Gallo also sees RumChata’s potential in hot drinks.

“One of the things, candidly, where we see real opportunity is with coffee,” says Lieb.

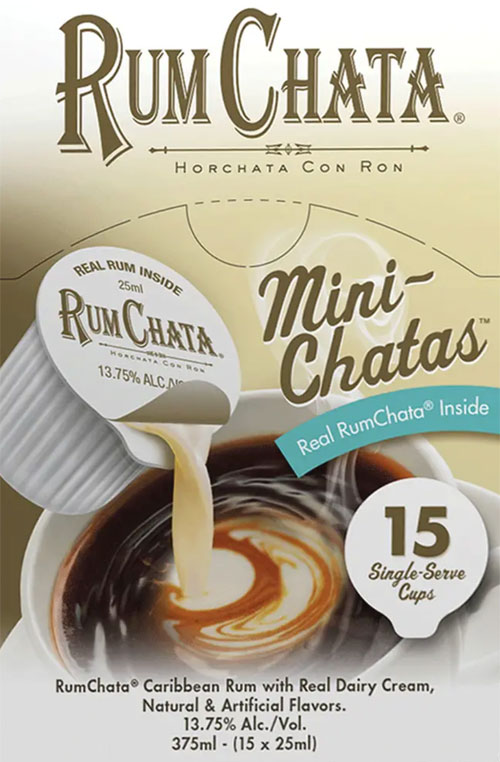

As early as 2016, Maas had introduced RumChata “Mini-chatas” 25-milliliter creamers that could be added to coffee. Today, the brand offers RumChata Cold Brew, a ready-to-drink alcoholic iced coffee. But, the easiest way to sell it, for Gallo, continues to be just getting people to try it.

“Once people taste it, they immediately love it, whether they know what horchata is or not,” says Lieb. “It has this quirky, fun Caribbean escapism that really resonates with people.”

That’s one reason the growth is moving at a much faster pace than Baileys, and may shockingly reach that stalwart one day. In fact, the whole cream liqueur category is surprisingly growing these days, despite this being the age of alternative milks.

“We see plenty of further opportunity,” says Lieb, noting that cream liqueur sales were up 20 percent in 2020. “The category has been totally flying under the radar.”

Today, the tireless Maas has started yet another business, Dancing Goat Distillery, along with his son Nick, located in Cambridge, Wis. They sell a solera-made Limousin rye; a three-botanical gin; a peppermint schnapps; and Travis Hasse Cow Pie, another rum-based cream liqueur meant to taste like Cow Pie chocolates, a popular Wisconsin treat. And even though he isn’t involved with it anymore, RumChata remains Maas’s first child, and he admits to still futzing with store displays if he notices they are sloppily set up. But, there’s no stopping RumChata’s success.

“I still think of RumChata as chocolate cake at a steakhouse,” says Maas. “You don’t go to a steakhouse to eat chocolate cake, you go to eat steak. But, if at the end of night they present you with a piece of chocolate cake, you eat it.

“You don’t go into a bar to drink RumChata, but when it’s presented to you, you go, ‘Oh yeah! Let’s drink some RumChata.’”

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free content platform and newsletter for the drinks industry, covering wine, beer, and liquor — and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!