The first step in introducing people to shochu, a traditional Japanese single-distilled spirit made from grains and vegetables, is to explain to them what it is not. Far too often, this process starts by informing people they haven’t had shochu when they think they have.

“Whenever I ask someone if they’ve had shochu before, nine times out of 10 they’ll say, ‘Yes! I’ve had it the last time I had Korean barbecue,’” says Paul Nakayama, president and co-founder of Nankai Group, which produces Nankai Shochu. “That’s when I have to gently tell them what they actually had.”

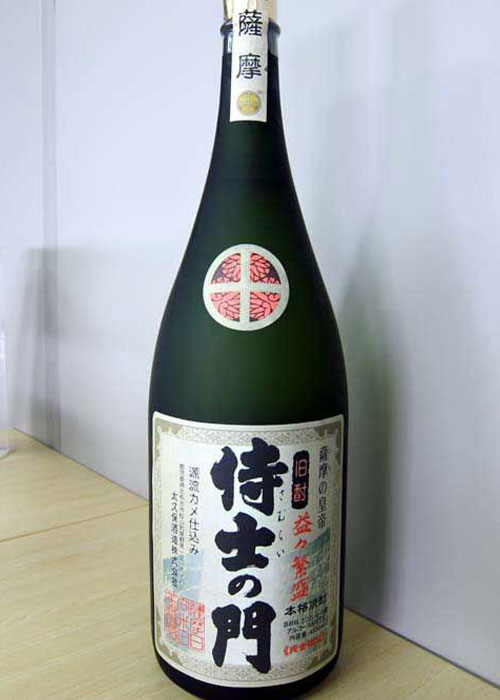

What they drank as they feasted on galbi and banchan was soju, the clear, multi-distilled Korean spirit traditionally made from grains and starches. It’s a common misconception. Soju and shochu’s categories are dramatically conflated in the United States, despite having dramatically different flavor profiles — soju is akin to a sweetened vodka, whereas shochu’s flavor wheel spins from robust earthiness to rum-like fruitiness depending on its base ingredient. This conflation is to shochu’s detriment, as it gets so engulfed by soju, the average imbiber has no idea it exists. Like a lot of oddities within the adult beverage industry, a law lurks behind this unfortunate muddle. The specific culprit here is a piece of California legislation that’s meant to expand restaurant drink programs but ends up leaving a delightfully complex spirit category languishing in obscurity.

Don’t miss a drop!

Get the latest in beer, wine, and cocktail culture sent straight to your inbox.

Shochu, Soju, the Law, and a Loophole

Shochu and soju have similar sounding names and possess ABVs lower than Western distilled spirits, so getting the two categories jumbled up would be an easy if not forgivable faux pas for the casual imbiber. California’s Type 41 liquor license — which allows restaurants to sell beer and wine — exacerbates this confusion and does so at shochu’s expense, all due to a law that expanded the license’s capabilities and led to decisions that may be considered myopic in retrospect.

In 1998, with the help of some lobbying by the Korean Restaurant Owners Association, a law passed that allowed restaurants with a Type 41 license to sell distilled spirits under 25 percent ABV. This stipulation made it possible for dining establishments to whip up cocktails using soju, which checks in at 24 percent ABV. This addendum provided shochu makers a loophole with a catch: Shochu could also be sold at these California restaurants — if the word “soju” appeared somewhere on the bottle’s labeling.

This loophole inspired shochu brands eager to get their bottles into California’s Korean and Japanese restaurants to slap the word on their bottles. It also caused a fundamental shift in shochu production, as distillers began reducing shochu’s ABV from its typical 25 to 24 percent to gain proper legal compliance. While these adjustments did allow brands to immediately enter California restaurants, decades of shochu semi-masquerading as a different spirit has hurt its ability to enter public consciousness as its own separate category. “It’s a double-edged sword,” says Nakayama. “So much of the shochu market depends on that loophole, but that same loophole stops the category’s growth.”

“It’s a definite ‘own goal,’” says Christopher Pelligrini, founder of Honkaku Spirits and author of “The Shochu Handbook — An Introduction to Japan’s Indigenous Distilled Drink.” “Unfortunately, we now have a generation of consumers in the U.S. that refuse to try shochu because they think it’s soju, and they don’t like soju.”

The Law and Its Influence

California’s law is a big reason for all this confusion between shochu and soju. Yet there are other bits of legal oddities surrounding both spirits, such as the way they’re treated by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) — or, more accurately, how they’re not treated. “Neither shochu nor soju are officially categorized by the TTB,” says Stephen Lyman, ambassador of Honkaku Spirits, author of the James Beard Award-nominated book “The Complete Guide to Japanese Drinks,” and, like Pelligrini, an American expatriate residing in Japan. “Gaining this categorization would literally require an act of Congress.” Such an act would be in shochu’s best interest: Categorization would likely bring about regulations on elements like labeling and production, which would theoretically compel California to amend the law and split shochu into its own category.

Still, it seems fair to view the California mandate as the impetus behind this categorical boondoggle for a couple of other reasons. Some of the bottles produced with these soju-as-shochu labels may land in California, but not all of them are destined for the Golden State. This means the category-lumping labels permeate across the country. California’s law has also inspired a similar mandate to appear on New York’s books.

As the world shrinks and curiosity about spirits around the globe grows, the law and its influence around the country have increasingly become a source of frustration for those seeking to grow American interest in the category. “I can’t overstate the impact that this blatant mislabeling has had on the shochu category,” Pelligrini says. “Because of it, we’re not starting at zero when we try to explain shochu to people like we would if we were explaining bourbon or gin. We’re starting at a negative number because there is so much wrong knowledge out there.”

At the same time, some industry professionals acknowledge that the issue was partially caused by the shochu industry, particularly in the law’s early years. “Unfortunately, shochu makers and distributors struggled to pay attention to a broader market that went beyond serving Japanese customers in Japanese restaurants,” says Kayoko Akabori, co-founder and shochu director of Umami Mart in Oakland, Calif. “Putting ‘soju’ on the label was initially helpful, but it wound up being a shortsighted decision because they weren’t mindful of what the shochu category could be in the long run.”

Working Toward Change

While the mandate requires the word soju to be printed on a bottle’s labeling, it doesn’t specify where or on which label. This creates a loophole within a loophole. Nakayama takes full advantage of this, printing “soju” on the back label of Nankai’s 24-percent-ABV, license-compliant shochu — effectively hiding the word from plain sight.

Of course, finding clever ways to work around the law while remaining compliant isn’t the long-term solution. Achieving a more permanent legal fix to the issue is the goal; according to Lyman, this may require a mixture of political maneuvering and patience. “We know a lot of mid-level diplomats in Japan,” he says. “As they move up the ranks, we’re hoping that they can possibly connect with the right people in the U.S. and bend some ears toward this situation.”

In the meantime, educating people that shochu is not soju — and definitely not what they drank the last time they had Korean barbecue — will have to suffice. The good news is that the efforts to do so seem to be paying off. Akabori says that attendance for her shop’s shochu club, Shochu Gumi, is robust and that 20 to 25 percent of her online shochu sales come from the Midwest, where shochu can be tough to acquire in person. This gives her hope that even with California’s law mucking up the works, shochu can grow and thrive as its own independent category. “People didn’t know about mezcal 10 years ago, and now it’s everywhere,” Akabori says. “The same thing can happen to shochu. It should happen, because it’s that special.”