Last year, Brad Bonds, the co-owner of Revival Vintage Spirits, a vintage spirits retailer in Covington, Ky., acquired a collection from the family of Frank Rizzo, Philadelphia’s controversial mayor from 1972 to 1980. There was Hennessy and banana liqueur from the 1950s, Crown Royal from the 1960s, and other assorted brandies, Scotches, and plenty of the sorts of gross liqueurs that were popular mid-century.

But Bonds was most intrigued by a 1953 bottle of Old Forester Bottled in Bond. Packaged in circular brown glass, a copper medallion inset on the neck, the paper label states that it had been privately bottled “especially” for Bill Rodstein’s Latimer Club.

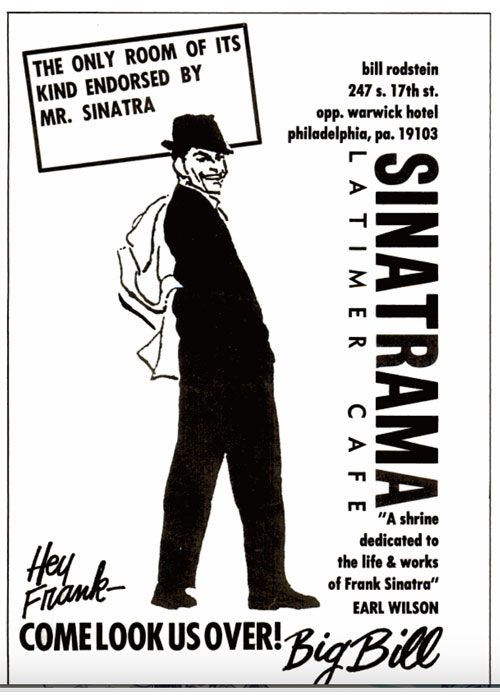

“And so I Google that, and I see it’s tied to Frank Sinatra,” Bonds says. More specifically, he would learn, it was tied to a Frank Sinatra-themed bar that was a hot spot in Philadelphia in the late 1950s through the late 1960s: Sinatrama.

Don’t Miss A Drop

Get the latest in beer, wine, and cocktail culture sent straight to your inbox.

Today, theme bars are seen as a nothing but pure gimmick. No serious drinker, no hip nightlife scenester, would be caught dead at, say, Margaritaville or the Beetlejuice bar. And is any single celebrity even famous enough these days to merit their own “nitery” (to borrow the lingo from the day)? They don’t make them like Frank Sinatra any more and no one has ever made a theme bar like Sinatrama.

Big Bill

William K. Rodstein, well over six feet tall and beefy in build, known as “Big Bill” to friends and strangers alike, had been on the periphery of the music business since the 1930s when he owned coin arcade machines and jukeboxes. He eventually started running nightclubs in Philadelphia. His first success was, fittingly, called Big Bill’s. He began stocking its jukeboxes with Sinatra records almost immediately after Hoboken’s favorite son began to release them, starting with 1946’s “The Voice of Frank Sinatra.”

“I never met him,” he told Billboard magazine in 1965. “I didn’t even know who he was. But I knew that I liked his singing better than any other singer. I loaded all my music machines with [Sinatra] records.”

It paid off. So much so that when, in 1951, Rodstein acquired the bar space inside the boutique Latimer Hotel on South 17th Street near Rittenhouse Square, he decided to go even further. He began to fill the small space with images of Sinatra, newspaper clippings, photographs, and torn-out pages from magazines. Over the years he added all of Sinatra’s records, books about him, and movie posters. The small room would grow to reportedly have the world’s largest collection of Sinatra memorabilia, including a lifesize stand greeting customers at the entrance (who, in turn, usually greeted the 2-D Frank with a kiss on the cheek).

The Latimer Cafe would casually, then formally, take the name Sinatrama. Almost immediately, the dark, smoky space began to attract a cool crowd, the last vestiges of the post-War, suit-and-tie Greatest Generation.

“It was your Martini and bourbon crowd. All the same stuff people drink today,” recalls Donald Moore, a longtime Sinatra enthusiast who began going to the Sinatrama as a teenager. “And everybody was drinking Jack [Daniel’s] of course because Frank drank Jack.”

Endorsed by Mr. Sinatra

By 1958, Rodstein had five different jukeboxes in the bar exclusively offering Sinatra records in them, an unparalleled collection of 800 songs, both common and deep cuts, available on 33s, 45s, 78s, and LPs printed on wax, tape, and acetate. Each jukebox earned about 50 bucks per week — a huge number for the day.

If no customer had purchased a new Sinatra song by the time the last one had finished, yet another jukebox would automatically play one, on the house. “The Lady is a Tramp” and “Come Fly With Me” were the most frequent choices. Rodstein was so proud of this collection that he would frequently claim it was literally impossible to name a Sinatra record he didn’t own.

“If I don’t have the Sinatra record you ask for, I’ll mow your lawn, shovel your driveway, walk your dog, or wash your car!” he claimed. Guests could also queue up any number of Sinatra audio interviews, both those that had appeared in standard media and more obscure off-air recordings. Rodstein had even interviewed Frank in 1958 at Capital Towers in Hollywood and put it on a record. Likewise, Rodstein could unspool film strips of Sinatra over the years and play them on a pull-down screen.

Sinatra was still alive, of course, arguably still at the height of his career. He’d released one of his biggest hits, “Come Fly with Me,” in 1958, won Grammy Album of the Year in 1959, and headlined “Ocean’s 11” in 1960 and “The Manchurian Candidate” in 1962. And, like a teeny bopper decorating their bedroom walls, Rodstein continued to add a near-daily supply of paraphernalia and images, magazine pages, celebrity shots, and news clippings to the bar space. (The men’s room was the only place that did not have Sinatra’s visage in it.)

“Was it a gimmick? Not at all,” says Moore, who points out that just this year, a legitimate restaurant group opened a Sinatra-themed bar and lounge in Nashville. Moore, professionally a hairdresser but also a bar owner of spots like Social Lounge in West Chester, Pa., always dedicates at least one wall in his spaces to Sinatra.

Ol’ Blue Eyes supposedly never visited Sinatrama himself — “The Only Room in the World of this Kind Endorsed by Mr. Sinatra” — even in 1960 when he accepted an award at the Sons of Italy hall just down the block. (Though, Moore disputes that.) Sinatra’s parents had visited, though, during that same trip. And Sinatrama was a regular celebrity haunt over the years, frequented by visiting athletes from Major League Baseball and the NBA, as well as a slew of on-tour performers, musicians, and comics.

Iconic Philadelphia DJ Jerry Blavat was a friend of Rodstein and a regular. Because of his own connections, he would often ferry visiting celebrities to Sinatrama late in the evening. “I remember taking (Don) Rickles there when he worked the Celebrity Room,” he reminisced to the Atlantic City Weekly in 2013.

Atlantic City was also home of the 500 Club, owned and operated by mob associate Paul “Skinny” D’Amato from the 1930s until the building burned down in 1973. The club’s main showroom, the Vermilion Room, frequently offered performances from Sinatra and his Rat Pack pals.

Souvenir from Sinatrama

On Aug. 5, 1962, Sinatra, Dean Martin, and Sammy Davis Jr. gave a special 4 a.m. performance, which Bill Rodstein just so happened to be attending. He recorded the show, pressed it to vinyl, and then gave away copies of the performance exclusively at Sinatrama. “Amateurishly produced [and] poorly packaged” reads the listing on the Esprit record collecting website, the album can be found with several different covers, some just pasted over top a repurposed record sleeve Rodstein must have had on hand.

Nonetheless, Sinatrama remains one of the rarest and most sought-after records among Sinatra collectors today. The fact that Nancy Sinatra’s lawyer, Robert A. Finkelstein, has tried to prevent the re-sell of any and all copies of the album, being that it was an unauthorized bootleg, only makes it more coveted.

“Insipidly titled ‘Souvenir from – Collectors Item,’ and inanely labeled a ‘Non Published Album, Not Available Anywhere Else’ this album is prized by Rat Pack collectors,” writes music historian Jerry Osborne.

By the late-1960s, America was changing. It was the Summer of Love, the Beat Generation, hippies and drugs, anti-war protests and counterculture music. Was there still room for a 50-something crooner in tailored suits? The Latimer Club and Sinatrama closed unceremoniously sometime in 1968 as far as I can tell, though there was not a single mention in any newspaper I could find.

Rodstein would die in 1969 at age 57 and, though he would garner several nice obituaries, he is mostly forgotten today. Except on a bottle of $10,000 bourbon still available at Revival — and in the legacy of Sinatrama, the greatest theme bar there ever was.